Between Gratitude and Ground

On Rest, Reconciliation, and Treading Trodden Trails

Inspiration Point

Carroll County, Arkansas

36°26'27.6"N 93°47'11.8"W

Hello Neighbors,

Today marks another day of driving, diverting, and diving into the details that dovetailed me into the great plains of the Texas Panhandle. I feel lucky to share this time and space with you, and deeply appreciate your company.

495 miles separate the cypress-scented shores of Beaver Lake from where I’m writing. The road between the Ozarks and Amarillo runs through a kind of in-between country, where what’s behind you still hums in your head and what’s ahead hasn’t yet quite taken shape. Somewhere along this stretch, I started thinking about gratitude. The kind of appreciation for life that comes after distance, and silence, and years of holding your breath.

There’s been a quiet reconciliation unfolding in my life lately. A loosening of what once was. It’s strange work, this softening. More wrinkles, maybe, hopefully a little more wisdom too.

I’ve come to think of this whole trip as practice in gratitude and ground, moving through landscapes that ask you to pay attention, to slow down, and to remember how beautiful this world can be.

Over the years, I’ve tried to focus on holding contradictions, the love and the fear that shaped me. The Heart Sutra calls it "two truths."

The Two Chambers of the Heart Sutra

In Madhyamaka Buddhism, there's a teaching called the Two Truths doctrine. It says that reality operates on two levels simultaneously: conventional truth (the everyday world of distinctions, names, and separate things) and ultimate truth (the deeper reality of interdependence, where all boundaries dissolve).

The genius isn't that one truth is more "real" than the other. It's that both are true at the same time. The wave is distinct from the ocean (conventional truth), and the wave is inseparable from the ocean (ultimate truth). Both accurate. Both necessary.

Something I've realized over the years unpacking CPTSD is that healing requires holding multiple truths. The harm from my childhood and adolescence was real. As was the love for me. As did the pain shape me. The same experiences that wounded me also gave me my particular way of seeing the world. My sensitivity, my depth, my drive to understand.

The Heart Sutra, one of Buddhism's most famous texts, puts it like this: "Form is emptiness, emptiness is form." Not form OR emptiness. Not one canceling out the other. Both, held together, creating the complete picture.

This is life. Not because it's comfortable. But because it's true.

‘As Above, So Below’ | Fall foliage at Lake Atalanta

Rogers, Arkansas

In the Country of No Return

The three weeks before Oklahoma City were spent in the Ozarks, around Beaver Lake in northwest Arkansas.

The Ozarks aren't a single mountain range. They're a vast highland plateau stretching from central Missouri down through northwest and north-central Arkansas, reaching into Oklahoma and Kansas. Over 47,000 square miles of ancient stone, dense forest, hidden springs, and winding rivers. The northern boundary sits near Columbia, Missouri. The southern edge extends well past where I camped at Beaver Lake, down toward the Arkansas River valley.

These mountains are old. Older than the Appalachians. Some of the oldest exposed rock in North America, worn smooth by 300 million years of weather and time.

The people who live here have always known something the rest of the world is just starting to remember: this landscape heals.

Long before Eureka Springs became famous for its Victorian architecture and metaphysical bookstores, the Indigenous peoples of this region, particularly the Osage, knew these springs and highlands as places of restoration. When European settlers arrived, they built towns around the same springs, marketing them as healing destinations. By the late 1800s, Eureka Springs was drawing thousands seeking cures for everything from tuberculosis to "nerve disorders."

That tradition never really left. It just evolved.

Today, the Ozarks hold a fascinating collision of cultures: old-line Ozark families whose roots go back generations, wealthy retirees seeking quiet mountain towns, artists and makers drawn to cheap land and natural beauty, bikers rolling through on legendary routes like the Pig Trail, and seekers of all kinds looking for alternative ways of living.

There's a place called The Farm, an intentional community that's been here since the back-to-the-land movement of the 1970s. Eureka Springs hosts an annual motorcycle rally that draws thousands. Crystal shops sit next to Baptist churches. Herbalists practice alongside conventional doctors. The same town that hosts a thriving LGBTQ+ community also has Confederate heritage tourism. It’s a place with a strong tradition of oral history, and hesitation of outsiders.

It's a strange, gorgeous, layered place. The kind of landscape that doesn't resolve its contradictions but somehow makes space for all of them.

One afternoon at Beaver Lake, I met Genesis, a fellow traveler working as the park attendant. Her pup Bailey became best friends with Judy, and we made daily trips up to the shower station to let them run around. She showed me her rock collection from Wyoming and shared everything she knew about the Farm. “Talk to Gerry”, I was told. “She’s the one you have to talk to.”

Super rad Beaver Lake neighbor Teri-Lynn

A camp neighbor down the way told me about the Arkansas healing triangle: Hot Springs, Eureka Springs, and Beaver Lake forming a geographical trinity of energy and restoration. She was moving from Colorado to start a healing center at each point of the healing triangulation. We spoke for an hour and a half while overlooking the lake. Family histories, what our parents were like. The state of the world. Places of refuge. Whether you subscribe to such ideas or not, there's something undeniable happening here. People come to the Ozarks to heal, to slow down, to search.

I was no exception.

The mornings at Beaver Lake rise slowly. You can see the mist and it tastes like the trees smell. Canadian geese were arriving, the first wave of migration south. Judy watched the shoreline. Maeve adapted to tent life like a Bushwick cat who'd been waiting her whole life to go country.

Before leaving Arkansas, I knew I had to photograph Thorncrown Chapel.

A Treehouse of Light

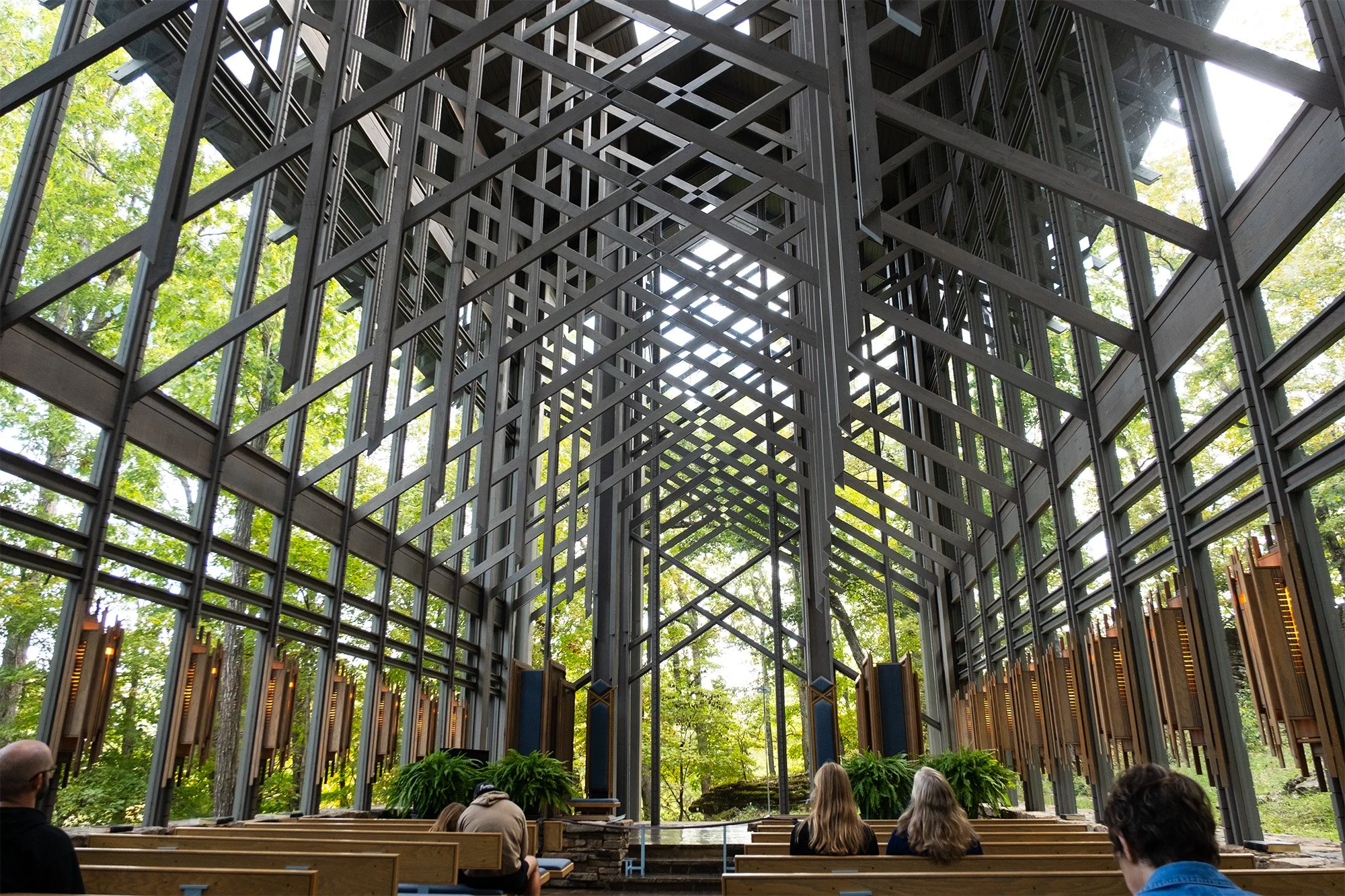

If you haven't seen Thorncrown Chapel, it's difficult to explain what makes it extraordinary.

Designed by E. Fay Jones, a student of Frank Lloyd Wright, Thorncrown sits in the forest outside Eureka Springs. It's a structure made almost entirely of glass and wood, 48 feet tall, with 425 windows and over 6,000 square feet of glass. The entire thing is held together by a lattice of wooden trusses that echo the trees surrounding it. The best way I can describe it is that “It is a work of art and an act of God, equal parts playful and transcendent.”

Jones designed it to be built without heavy equipment. Every piece of material had to be carried through the forest by hand. The result is a building that feels less constructed than grown. It doesn't impose itself on the landscape. It reveals it. The logic of the building tells me that it’s designers revere nature as the highest form of intelligence. It is a place that makes you weep without warning. You feel something when you are sitting in that building—an overwhelming sense of grace and love.

“It is a work of art and an act of God, equal parts playful and transcendent.”

Etymological Note

The word "religious" carries its meaning in its very roots. From the Latin religare—"to bind back" or "to tie fast"—it shares ancient kinship with the Sanskrit yuj, meaning "to yoke." This linguistic archaeology reveals religion not as abstract belief but as practiced connection: a yoking together of the human and divine, of individual and community, of present moment and eternal pattern.

Like oxen bound by a yoke to pull in tandem, the religious impulse is global, and suggests a chosen constraint that enables greater work than could be accomplished alone. It is both burden and partnership, limitation and liberation. A binding that, paradoxically, sets us free to move in harmony with something larger than ourselves. My religion is with the squirrels and the deer, the geese and the butterflies, the water and the sky.

Alter at Thorncrown Chapel

What strikes me most about Thorncrown isn't the technical achievement, though it's considerable. It's the intentionality. Every detail, from the custom sconces along each pew to the way the wooden trusses mirror the tree trunks visible through the glass, serves a single purpose: to make you present. To make you notice light. To make you aware of where you are, and what you are.

Inside, Bibles line each row of pews. Small, worn, available. An offering, not a demand. The space holds its Christian origins loosely enough that people of all faiths and no faith come here to sit in silence, to witness light moving through glass, to be in a space designed entirely around paying attention.

This is what sacred architecture does at its best: it creates conditions for awareness. Not through dogma but through structure. Through light. Through the simple act of making a space where beauty is unavoidable.

The drive through the Ozarks in mid-October, with rolling hills giving way to dense trees and light filtering through in shafts, it's the kind of road where you want to pull over every half mile just to look.

Inspiration Point lookout and locks

I arrived at golden hour, camera ready, Judy in tow.

The chapel was closed for a wedding.

I stood there laughing. Of course it was. I was waiting for this moment for two decades. What's one more good night’s sleep?

The next morning, I returned. Early. Empty. Quiet. The light was different, cooler, softer, but the space was entirely mine for the first few minutes. No one else there. Just the structure, the forest, the silence, and the slow work of paying attention. I wept.

Sometimes the detour is the point. Sometimes you have to come back the next day, or the next year, or the next decade to get what you came for.

‘Economies in transition’

Amarillo, Texas

Of Stone & Sky

Somewhere between the Ozark stone and Amarillo blue sky, I started to understand what can’t be undone. The Ozarks teach you that healing and history share the same soil. This is a country of no return.

After Thorncrown, I drove south toward Oklahoma City, then Amarillo.

The route traces, in part, the Trail of Tears. Between 1830 and 1850, the U.S. government forcibly removed over 100,000 Indigenous people from their ancestral lands in the Southeast, the Ozarks included, marching them west to designated "Indian Territory" in what's now Oklahoma. The Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek, and Seminole nations all walked these routes. Thousands died along the way from disease, starvation, and exposure.

The landscape itself tells the story. As you drive south and west from the Ozarks, the terrain shifts. The dense forests and spring-fed streams give way to flatter plains, the sky opens wider, the green thins out. This wasn't accidental geography. It was policy. The government wanted the fertile lands, the forests, and the water. They still do today. They pushed entire nations into territory they deemed less valuable. Watching the news in OKC, I see analogs in today’s public hearings with angry residents warnings of what the construction of a data center in their neighborhood will do.

The Ozarks were home to the Osage for generations. They knew every spring, every cave, every hunting ground. When they were made to leave, they didn't just lose land. They lost the specific relationship to place that had shaped their culture for centuries.

I thought about this as I drove. About what it means to be displaced. About what it means to choose to leave versus being forced out. About the fact that I'm driving this road by choice, in a Subaru packed with my animal crew and gear, calling it a "journey," while this same route was once walked by people with no choice, no Subaru, no romantic story about searching.

The freedom to search is a privilege. The ability to frame displacement as adventure is a privilege. I don't forget that.

By Friday afternoon, I was checked into a hotel near Mercy Hospital in Oklahoma City. I dropped by on the off chance we could meet for three minutes.

She'd already left for the day.

The hospital staff were kind. They took my name, my story, a message. "Someone will call you Monday."

Mercy Hospital

Oklahoma City, OK

Rest, Resisted

Saturday morning, I woke up in the hotel room. Everyone was fed. I'd showered. The girls were napping. I turned on the TV. Independence Day was on FX, complete with loud commercials.

I sat there watching it like a person living in civilization.

And I realized: “This is rest. I should do this more often.”

Not doing nothing. Not forcing productivity. Just being. Letting my nervous system settle. Allowing space between one thing and the next.

Bowling nuns of Mercy Hospital

Tricia Hersey, founder of The Nap Ministry, writes: "Rest is resistance. Rest is a form of reparations. Rest disrupts and makes space for invention, imagination, and revolution."

I've been thinking about this all weekend.

I got my first job when I was young. I've worked every day since. I cannot remember a time when I wasn't working, planning the next thing, figuring out how to build it, and how to keep moving forward.

American culture teaches us that rest is laziness. That productivity is virtue. That if you're not grinding, you're failing. We've built an entire economy on the idea that your value is determined by your output.

But rest isn't the absence of productivity. It's the foundation of everything worth building.

You cannot lead a life worth living if you never stop to notice you're living it right now. You cannot build something meaningful if you're too exhausted to remember why it matters, why you woke up today. You cannot ask the questions that need asking if you never create space for them to surface.

Rest is essential. Not optional. Not something you earn after you've worked hard enough. Essential.

And rest, for people like me who've been in survival mode since childhood, feels dangerous. Letting your guard down means something bad might happen. Stopping means falling behind. Being still means being vulnerable.

But Saturday morning, watching Hollywood save the world while commercials interrupt every twelve minutes, I understood something new: Rest isn't the absence of doing. It's the presence of safety.

This weekend in Oklahoma City has been that practice. Doing laundry. Eating real meals. Letting the girls nap. Watching movies. Writing. Waiting. Being here without an agenda beyond enjoying my time on this rather lovely little planet.

‘Self Serve No-1’

Texas–New Mexico border

The Way Walks Backwards

A hiker I follow and learn from once said, “The trail provides.”

In long-distance hiking communities, the phrase has become a kind of mantra. When you need water, you find a stream. When you need shelter, a trail angel appears with a place to stay. When you’re out of food, someone shares what they have. The trail provides.

Over time, I’ve fallen in love with this phrase. Surrender, and the path will present itself.

It sounded mystical at first. And I’ve been thinking about what that phrase actually means to me.

‘Self Serve No-2’

In Taoism, there’s wu wei, or effortless action. Not passivity, but alignment. Moving so fully with the natural flow of things that action arises without force. The river doesn’t try to flow. It flows because that’s what rivers do.

Zen teaches the same thing in simpler words: when you walk, walk. When you sit, sit. Don’t wobble. Be so present to what’s happening that the next right step becomes obvious. You don’t force the path. You walk it. And in walking, the path appears.

Indigenous traditions speak of reciprocity with the land, the understanding that if you show up with respect, if you pay attention, if you give back, the land provides. Not because it’s magic, but because you’re in right relationship.

The Stoics add another lens. You don’t control what happens. You only control how you respond. The trail provides not because the world always works out, but because you become the kind of person who can work with whatever the world gives.

Different names for the same truth. The providing isn’t external. It’s relational. It’s something that emerges between you and the path, you and the moment, you and the challenge right in front of you.

The trail provides because you keep walking.

Because you pay attention.

Because you ask for help when you need it.

Because you adapt.

The trail provides because you are the trail.

The resilience isn’t mystical. It’s relational. It comes from the refusal to quit. From the willingness to be vulnerable enough to ask for what you need. From showing up even when you can’t see what’s next.

The trail provides because I walk the line.

Until next time, keep searching.

‘Self Serve No-3’